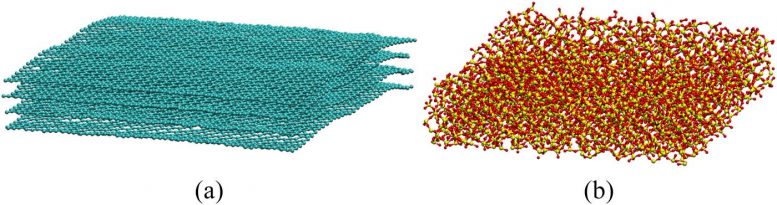

Doctoral student Neil Mehta working with Prof. Deborah Levin looked at two different materials that are commonly used on the exterior surfaces of slender bodies — smooth graphene and rougher quartz. In the model, these materials were attacked by aggregates composed of argon atoms and silicon and oxygen atoms to simulate ice and dust particles hitting the two surface materials. These molecular dynamics studies taught them what stuck to the surfaces, the damage done, and the length of time it took to cause the damage — all at the size of a single angstrom, which is basically the length of an atom. Why so small? Mehta said it’s important to start by looking at “first principles” to thoroughly understand the erosive effects of ice and silica to graphene and quartz surfaces. But those who simulate fluid dynamics use lengths that are several milli-meters micrometer to cm — so scaling up the physics of the MD models was urgently needed. The excitement about this work is that it was the first to ever do so in this application. “Unfortunately, you can’t just take the results from this very tiny angstrom level and use it in aerospace engineering reentry vehicle calculations,” Mehta said. “You can’t directly jump from molecular dynamics to computational fluid dynamics. It takes several more steps. Applying the rigor of kinetic Monte Carlo techniques, we took details at this very tiny scale and analyzed the dominant trends so that larger simulation techniques can use them in modeling programs that simulate the evolution of surface processes that occur in hypersonic flight, such as erosion, sputtering, pitting. “At what rate will these processes happen and with what likelihood will these types of damages happen were the key features that no other Kinetic Monte Carlo or scale bridging has used before,” he said. According to Mehta, the work is unique because it incorporated experimental observations of gas-surface interactions and molecular dynamics simulations to create a “first principles” rule that can be applied to all of these surfaces. “For example, ice has a tendency to form flakes, ice crystals. It creates a fractal pattern because ice likes to stick to other ice, so it’s more likely that the water vapor will condense next to an ice particle that is already on the surface and create a trellis-like feature. Whereas sand just scatters. It doesn’t have any preference. So one rule is that ice likes to stick to other ice. “Similarly, for degradation, the rule on graphene is that damage is more likely to occur next to pre-existing damage,” Mehta said. “There are several rules, depending on what material you’re using, that you can actually study what happens from an atomic level to a micrometer landscape, then use the results to implement in computational fluid dynamics or any long, large-scale simulation,” Mehta said. One application for this work is for research on how to design thermal protection systems for slender vehicles and small satellites at altitudes near 100 km (62 mi). Reference: “Multiscale modeling of damaged surface topology in a hypersonic boundary” Neil A. Mehta and Deborah A. Levin, 30 September 2019, Journal of Chemical Physics.DOI: 10.1063/1.5117834